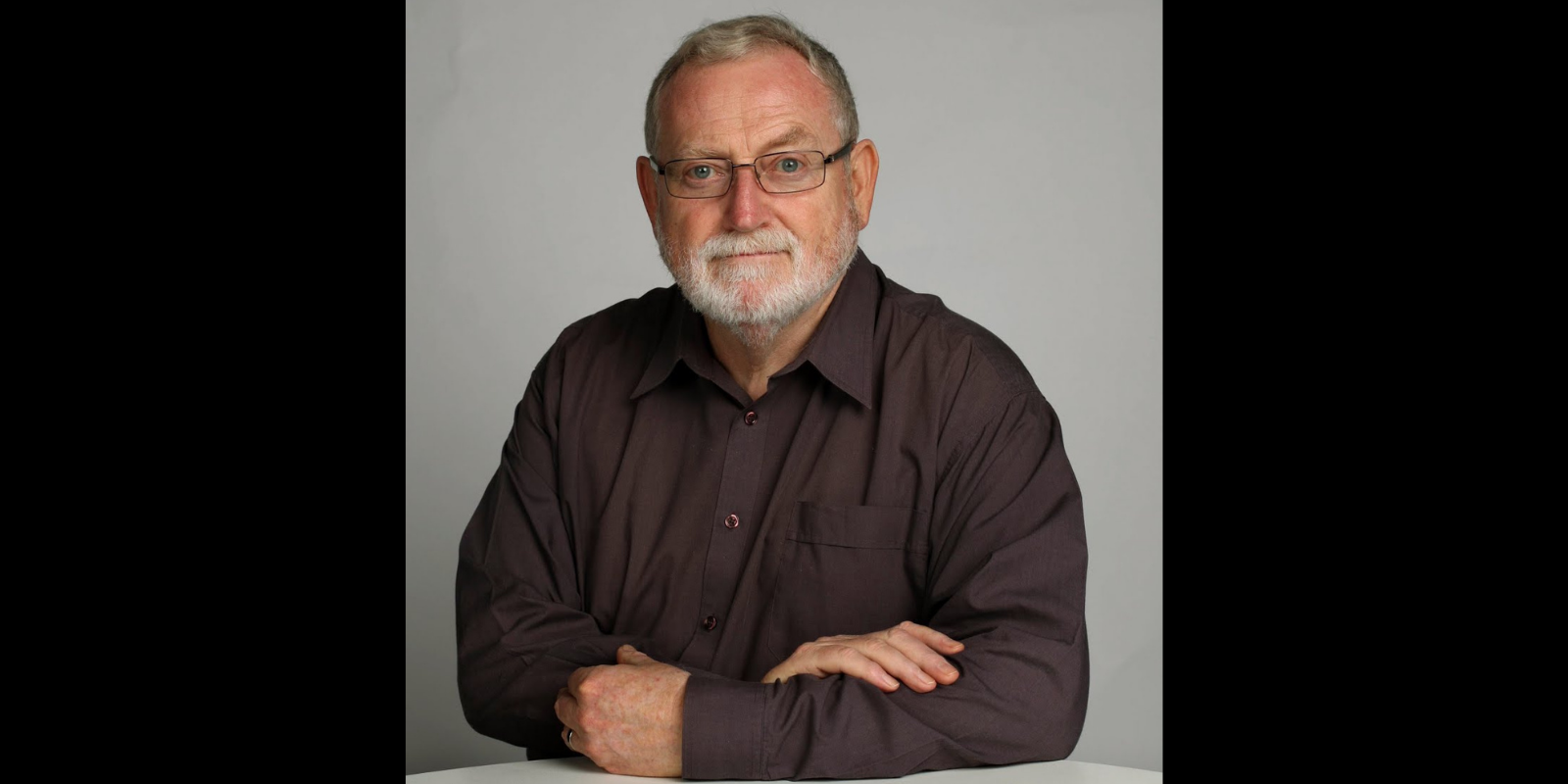

2020 winner of the Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism Award.

For more than 40 years, Ross Gittins has been the guru of explanatory journalism. Arguably, in the field of economics, he is also the father of the genre in Australia, making economics and public policy a must-read by making it accessible.

He has an unparalleled ability to demystify complex and technical topics to help his readers understand economics and decide whether they agree with particular policies.

This has made him the doyen of Australian economic commentators, connecting often esoteric theories with everyday life and reminding a financially obsessed nation about ethics and doing the right thing. In the time of the global pandemic, which has triggered a global recession, his razor-sharp analysis has never been more important.

In the words of former Treasury secretary Dr Ken Henry: “Forty years of beating up on economists has only endeared him to this most precious of professions. There are two reasons. First, we have been in awe of his powers of exposition; he outclasses all of us. Second, Ross has spoken to us as a conscience …”

The Walkleys spoke to Ross shortly after he received the award for Outstanding Contribution to Journalism about his motto of always “serving the reader”, holding politicians and the finance and banking industries to account, and his 40+ year career in journalism.

Interview by Margot Saville.

Watch colleagues at The Sydney Morning Herald pay tribute to Ross’s gift for economic analysis, his openness to mentoring young journalists, and his relaxed approach to both high-pressure situations and footwear.

Ross, can you tell me how long you’ve been a journalist? How did you get your start?

I got my start in journalism because I took a year off from my career as an accountant. And I did the first year of a journalism degree at UTS. At the end of the year, after I’d become the co-editor of the student newspaper, my journalism lecturer said to me, “Are you gonna go back to accounting or would you like to get a job in journalism?” And I hadn’t really thought about it, but he made me think about it, and he said, “Well, if you’re interested, I’ll put in a word for you to The Sydney Morning Herald.” That’s how I became a journalist.

How long have you been working at The Sydney Morning Herald?

46 years. And not for anybody else. It’s the entirety of my career as a journalist.

So how many editors have you worked for during that time?

I haven’t had the time to get down and make a list. It’d be a lot. It’d be … I guess it’d be at least 20. One of them only lasted 24 hours, but I can remember his name and put him on the list.

“What they all say to me is that, ‘You’re the only economist we can understand’. I think someone will write that on my gravestone… I think the secret of my success has been that I have been completely focused on the reader.”

Lisa Davies, Ross Gittins and Chris Janz at The Sydney Morning Herald offices for 2020 Walkleys Awards.

You get a lot of feedback from the public, what’s the thing you think that you give to the readers of The Sydney Morning Herald? What’s the most important thing they can take away from reading your columns?

Well, what they all say to me is that, “You’re the only economist we can understand.” I think someone will write that on my gravestone. And it’s not a bad thing to have them write, but I think the secret of my success has been that I have been completely focused on the reader. My motto is ‘serve the reader’.

The great temptation in journalism is to write to impress other journalists, to write to impress your contacts. If you’re an editor the great temptation is to to put a paper together or whatever it is, a news bulletin together, to impress other editors. I think if you focus on the reader and put top priority on having them understand and like and appreciate what you’re doing, you get pretty well rewarded.

Ross Gittins at the start of his journalism career in the 1970s.

You’ve been there for 46 years, do you plan to be there forever? Any plans to retire and, you know, move to the farm or something?

I plan to walk out of there the day I realise that I’m starting to lose my marbles. Fortunately, it hasn’t happened yet.

“I plan to walk out of there the day I realise that I’m starting to lose my marbles. Fortunately, it hasn’t happened yet.”

What’s the most important thing, do you think, about the kind of journalism that you do?

I think one of the things I do is I play my part in holding power to account. I write about economic policy, I spend a month going through the budget, looking at it, turning it inside out. If there’s any creative accounting in there, I write about it.

“I spend a month going through the budget, looking at it, turning it inside out. If there’s any creative accounting in there, I write about it.”

And that’s all about me trying to say, “I’m not gonna let any of these politicians mislead my readers.” If I see a politician saying misleading things, it’s my job to point that out to my readers. That’s what I try to do and I think that they appreciate it. And I certainly am not there to make the politicians like me. That’s one of the great advantages of writing about Canberra politicians, but not living in Canberra.

Have you had some robust feedback from some of the politicians you’ve covered?

I have, but I’ve been surprised at how mild they were. People used to always talk about how Paul Keating would ring them up and abuse them when he was the Treasurer to the Prime Minister. Everything he said to me was said more in sorrow than in anger. And that goes for the current controversy about superannuation, because he [Josh Frydenberg] and I don’t see eye to eye on that one.

Do you have any advice for younger journalists coming up?

My advice to younger journalists is that there’s more to good journalism than getting scoops. That there are lots of other ways to play a valuable role, a role that is valuable to the readers. A role that readers and listeners are prepared to pay for, which they have to be [prepared for]. We need readers to be prepared to pay for news these days. So you focus on their needs, which is not the same as telling them what they want to hear.

I used to have a motto that went, “I let the readers ask the questions, but I won’t let them determine the answers.” And that’s a good attitude to have. You address issues that are important to the reader, but you may well be telling readers something that they’re not quite sure they want to hear.

“I used to have a motto that went, “I let the readers ask the questions, but I won’t let them determine the answers.” And that’s a good attitude to have.”

Watch Ross Gittins’s acceptance speech for the 2020 Walkley Award for Outstanding Contribution to Journalism.

What’s been the best part for you of winning Outstanding Contribution to Journalism Walkley Award, and the recognition of your peers?

One of the things that’s good about it is that it’s a recognition of the contribution of economic journalists and economic commentators. I might be wrong, but I don’t think many people [in this field] before me have had a recognition from the Walkleys.

But when I talk about recognition of economic and financial journalism, I have to pay my respects to Adele Ferguson because she’s had plenty of recognition. I believe that all journalism should be investigative. If you’re fighting someone, you got to be reasonably certain that they’re saying the right thing and if they’re trying to say something that you think is misleading the readers, you’ve got to find a way to balance that with something that doesn’t mislead them.

But Adele has has been widely recognised because she has demonstrated that investigative reporting is very important in the field of business and finance, and she’s found plenty of things that need to be exposed to the readers. She sets a great example for young economic and business journalists.

One last question I have to ask — what was the nature of your disagreement with Keating?

About increasing the amount of compulsory [superannuation] contributions. They’re already adequate. They’re not adequate for every woman whose career is interrupted, but in general, they’re adequate. The superannuation industry has a huge vested interest in persuading the politicians to compel people to put more and more of their salary into the hands of the fund managers because they take a little clip out of every dollar. And for some reason I don’t think it’s terribly honourable.

The union movement, and indeed, the entire labour movement has just thrown in their lot with all the banks and all the fund managers who’ve made an absolute fortune out of managing that money. The vigour with which they’re insisting that people ought to be paying a lot more — and those people don’t care whether you’ve got enough, they’ll try and tell you that you haven’t got enough.

But, in fact, when people look at it, they say it’s actually not inadequate. You don’t need a lot more than that, if you did more to reduce the costs of managing the fund — which of course would come out of the salaries of all the people who earn far more than the rest of us working in that industry. I don’t necessarily mean union secretaries on the board of super funds, but it seems like their getting their cut too.

Read all the 2020 Walkley Award-winners here.

Ross Gittins is the Economics Editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and an economic columnist for The Age. He is a winner of the Citibank Pan Asia award for excellence in financial journalism and has been a Nuffield Press fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge, and a journalist-in-residence at the Department of Economics at the University of Melbourne. Ross is frequently called upon to comment on the economic issues of the day and has written and contributed to many books and periodicals. In September 2011, Ross was awarded an honorary doctorate, receiving a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa from Macquarie University.

Ross Gittins is the Economics Editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and an economic columnist for The Age. He is a winner of the Citibank Pan Asia award for excellence in financial journalism and has been a Nuffield Press fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge, and a journalist-in-residence at the Department of Economics at the University of Melbourne. Ross is frequently called upon to comment on the economic issues of the day and has written and contributed to many books and periodicals. In September 2011, Ross was awarded an honorary doctorate, receiving a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa from Macquarie University.