2025 marks 70 years of the Walkley Awards, so throughout the year we’ll be finding some Walkley-winning gems from our archive to highlight.

As we looked back on the first Gold Walkley-winner, Catherine Martin (1918-2009), we found this obituary penned by Helen Trinca for The Walkley Magazine in 2009 almost impossible to excerpt. So here it is, reproduced in full.

At the top of her grade

Catherine Martin turned the health round into front-page news, writes Helen Trinca.

It’s odd the things you remember about people. I had scarcely thought about Catherine Martin since I left the paper we both worked on, The West Australian, 30 years ago, But when I learnt of her death in April at the age of 90, two memories came flooding back; Catherine declining to leave her contacts for the reporter who filled in when she was on leave; and the fact she was for a long time one of the very few female A-grade journalists in the newsroom.

Martin had a brilliant career – as medical writer for The West she won four Walkleys, was awarded an MBE and raised three children – and she had been a household name in Perth for a generation.

But somehow the woman I first saw when as a new cadet I walked into The West’s newsroom in 1971 seems defined to me by her ferocious protection of her round (in Roy Gibson’s obituary for The West, our colleague Jill Crommelin mentioned the withheld contacts – I suspect it was she who had to fill in for Martin) and the grading that set her apart from the great bulk of her female colleagues.

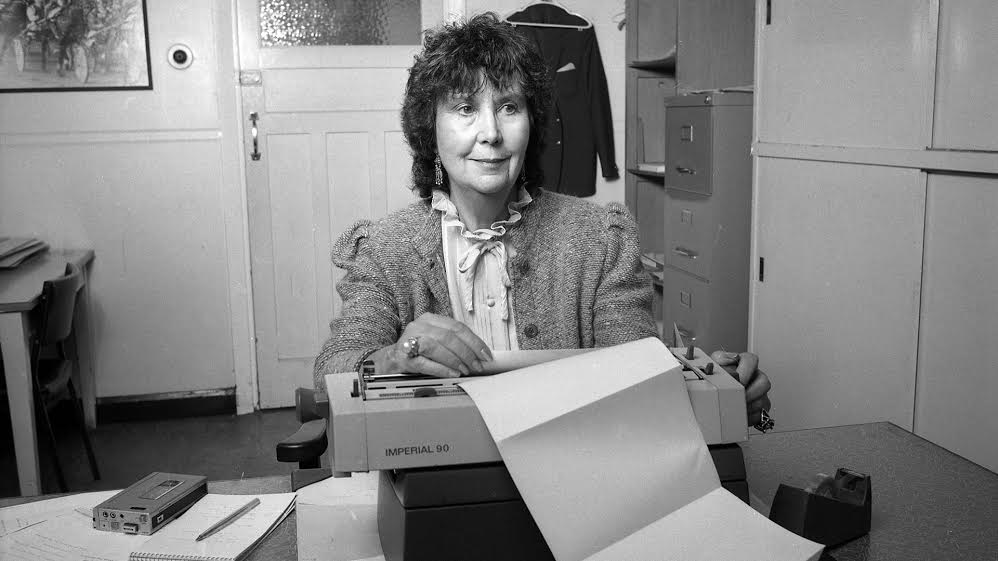

In those days she was in her early 50s – petite, dark-haired, rather funky glasses on the end of her nose – and quick in mind and movement. Catherine – only older colleagues called her Kit – sat straight-backed at her desk just inside the swing doors that opened from the corridor into the newsroom. It was an extraordinarily exposed, noisy and draughty position for a busy reporter and it must have been hell trying to do a phone interview, but then again, we rarely conducted business on the phone. Pre email, pre fax, it was all about relationships and contacts nurtured by face-to-face conversations. Martin certainly spent hours tramping around hospitals rather than in the office and it doubtless helped her win the confidence of her medical contacts.

She had a terrific work ethic and determination to succeed: her earlier life had had its share of challenges.

She would have been about 21 when she walked into the London offices of the Associated Press of America during the Second World War and talked her way into journalism. She had shorthand and typing and spoke French. In 1943 she joined the US Office of War Information and, at the end of the war, the United Nations Secretariat in New York, working in Europe and the Middle East.

She met her future husband in Haifa. He was Czech, an interpreter at the War Crimes Commission in Nuremburg, and the sole survivor of a family lost in the Holocaust. Soon after they married the couple migrated to Australia and had three children, but her husband died suddenly in 1957 and, forced to find a way to support her family, Martin found herself back in journalism with Perth’s morning newspaper.

By the 1970s she was a star. We were in awe, not just of her prodigious output but of that A grading. It was the era of the tightly structured and controlled wages systems. A four-year cadetship led to the graded system of D, C, B, A and A1. In The West newsroom in the ’70s, despite the fact that about half of us were women, there were one or two female A grades and a mere handful of Bs and Cs, while all the other women clustered around the D-grade level. Martin’s A gave her enormous status. Later, she would fight hard, staging a one-person strike, for her A1.

It would be convenient but wrong to see Martin as a standard bearer for women. I tend to see her rather as an individual acutely aware of her value to the paper: she had, after all, taken the “soft” round of health to a level comparable in impact to the state political round and even police rounds.

Where she was indeed a pioneer was in reporting on a subject which only now, three decades after she wrote about it, is truly being accorded just attention.

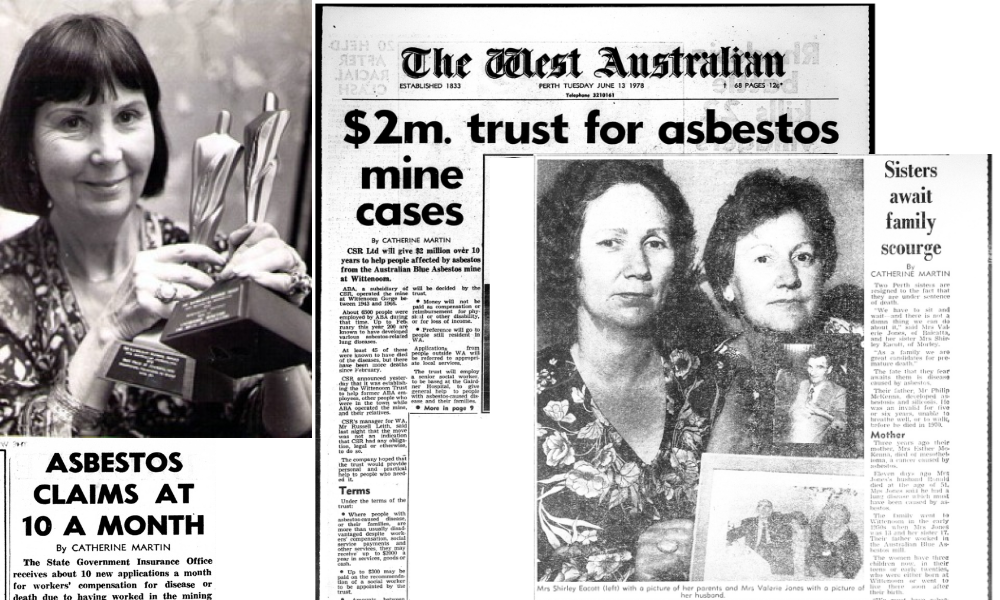

The subject is asbestos-related disease, about which Martin first wrote in 1978. Her front-page story in The West on the high incidence of death and illness among workers at the Australian Blue Asbestos mine at Wittenoom Gorge in WA won her the inaugural Gold Walkley that year and was just the start of a series of influential articles on the issue.

The “asbestos” Walkley was not her first. In 1973 she had won a Walkley for a series of articles on health services in the remote north-west of the state. Two years later she had won again for articles on the Tronado machine which was being used for the treatment of cancer. John Tonkin, the then Labor Premier, had backed the machine but it was being challenged by senior medicos in Perth. It was Catherine Martin who got the story. Her Walkleys were just part of a suite of prizes and awards (including an MBE in 1982) that she won throughout a highly successful career that concluded with her retirement in 1986.

But the Catherine Martin stories I remember most vividly were the human stories that then – as now – make the medical round such a buzz for readers as well as reporters.

It seemed that every few days back then the page-one picture story carried her byline and spoke of the child saved in a radical new procedure at Princess Margaret Hospital or of a successful treatment at Royal Perth or Sir Charles Gairdner. (Such was her clout that colleagues joked that some surgeons held back operations till she got back from holidays.)

They were stories full of the valour, courage, skill and compassion of those developing and using the new technology of medicine. Martin knew how to dramatise and she knew how to get those yarns onto page one. Those stories were as central to The West in those days as Paul Rigby’s cartoon and Kirwan Ward’s sketch were to the afternoon newspaper, the Daily News, in the ’60s.

They were stories pitch perfect for her audience, conveying information and building pride in medical progress and emerging technology. They seem as important as her prize-winning, investigative work. A journalism student could do worse than dig them out of the archives and analyse their impact on the attitudes of a generation of readers of The West.

This obituary was first published in The Walkley Magazine in 2009, written by Helen Trinca, then-editor of The Weekend Australian Magazine.