Winner of the 2019 Walkley Award for Headline, Caption or Hook

Baz McAlister at the 2019 Walkley Awards (Photo: John Donegan)

Writing tabloid headlines is an art form and Baz McAlister’s wordplay is an editor’s dream, selling even the softest stories with puns and punch.

A story about a fallen donkey that had to be winched out of a septic tank was a gimme (“Time to Haul Ass”), while McAlister’s deft touch on a traditional saying succinctly summarises a story about Adani mine approvals delayed by environmental approvals regarding a black-throated finch (“Give ‘Em a Finch and They’ll Take a Mine”).

And, hello, finding a way to insert a Lionel Richie earworm into a yarn about a prison fight over a mealtime incident might be downright genius (“Halal… Is it Meals You’re Sooking For”). We spoke to Baz about the thrill of a perfectly-tuned headline, his favourite-ever headers, and the similarities between a newspaper deadline and a comedy club stage.

If your interest is piqued to hear from the man himself about the delicate art of headline crafting, he’s hosting a free Walkley Masterclass on headline writing over Zoom on June 9. Registration is free but spots are strictly limited so get your name down swiftly over here.

How do you write a headline? What’s your process? You’re given the story and artwork or photos, and then you have to come up with a headline?

That’s right. I get the story and photos, and if any artwork is needed I work with a graphic artist to create it. From the moment it lands on my desk, my brain is churning through possible headlines. From the moment I’m awake in the morning, I’m engaging in wordplay inside my head, often to the consternation of my wife. Even when my brain is idling, it’s sparking infinite, invisible lines between the subject at hand and everything else I’ve ever heard – film quotes, song lyrics, sayings, fables, pop culture references and jokes. It’s a blessing and a curse. But it sure comes in handy for writing newspaper headlines.

Some headlines need a lot of processing power. However, I’ve had other stories land on my desk where as soon as I’ve heard the concept, I’ve got the headline, and I couldn’t do any better if I agonised over it for an hour. For example, the night editor approached me one shift saying: “I’ve got a fun one for you, it’s about a donkey that fell into a septic tank and had to be pulled out on a rope, but we need to get it on the page fairly quickly,” and I immediately said, “Time to haul ass, then.” I won the Walkley partially on the strength of that one.

How much time do you have to work? What kind of research might you do?

How much time do you have to work? What kind of research might you do?

90 percent of the time when writing a headline, there’s a looming deadline, and I have a lot of other work to do – subbing, writing captions, getting the layout right – but I will always take the time to brainstorm and offer up my very best headline, sometimes one that pushes the envelope in terms of being risqué, or bold, or niche. Then, once I have keyed my best into that blank space on the screen, and the page has been proofed, often comes the hard part: convincing the deputy editor, editor (and occasionally a team of lawyers on the end of a phone) that this is the way to go. That’s a fight that generally reaches its raging conclusion well above my pay grade, so it’s always handy to have a second-best backup headline on deck in case rejection is imminent.

Sometimes it’s fun and beneficial to bounce headline ideas back and forth with colleagues. I’ve only been in Australia for 15 years so I’ll often defer to their judgment on my usage of Aussie slang. For every headline that goes to print, there are usually 30 that don’t, and probably half of those are unprintable. Bouncing ideas off colleagues is a critical part of the process. It’s the same with headlines as with jokes: if you have to explain it to your peers, it’s not working.

“For every headline that goes to print, there are usually 30 that don’t, and probably half of those are unprintable”

What do you enjoy most about the craft of headline writing?

I’d rather write a headline that a dozen people think is genius than one a thousand people think is acceptable, so I’m always pushing myself. As a naturally creative person, I find headline writing is often the biggest outlet for that creativity in my current job. I also enjoy the reactions of my colleagues on the production team to the headlines I come up with. These are some of the smartest, wittiest, quirkiest people I know, and also some of the most cynical and exacting. If I can get a laugh out of them, or a compliment, I’m buzzing.

When you put a headline out into the world, you have no idea how it’s going to land, but often this small audience of 20-odd colleagues can give you a sense of that. I’ve done some stand-up comedy, and that’s part of what I loved about it: the instantaneous reactions from an audience to a piece of material. A newspaper production deadline, for me, is now like a bright comedy club spotlight shining in my eyes: an ultimatum to get out there and perform.

“A newspaper production deadline, for me, is now like a bright comedy club spotlight shining in my eyes: an ultimatum to get out there and perform.”

What would you say is the most important aspect of the craft that young/aspiring headline writers need to learn?

It’s a difficult skill to jump right into, but with my specialty, tabloid headlines, you need to get bums on seats with just a couple of words. Hook the reader in – the reporter who wrote that story is relying on you to tell readers why they need to be interested in it. Do it any way you can. Think outside the box. But don’t cheat: you have to tell the story and sell the story at the same time. Be as clever as you can with everything except death and grief. And consume! Read everything, listen to everything, watch everything, take everything in, so you have more ammunition in your arsenal.

You’ve had a long career as a writer and editor across newspapers and street press – in the span of that career, are there any pun-tastic headlines or captions that stand out as your favourite/s?

You’ve had a long career as a writer and editor across newspapers and street press – in the span of that career, are there any pun-tastic headlines or captions that stand out as your favourite/s?

One of the first headlines I remember writing was on a profile of the writer Stephen King’s son, Joe Hill, insisting on forging a career on his own terms and not trading on his famous father’s name. THE MAN WHO WOULDN’T BE KING leapt to mind, and it’s one of the earliest headlines I can remember being ecstatically happy with.

Some of my favourite headlines end up being ones that disproportionately amuse myself. I remember a story where a team of our reporters reviewed and rated barista coffee against coffee from a pod machine: my headline was CREMA VERSUS CREMA, and seriously I couldn’t stop laughing and I felt like taking the rest of the day off after that one.

“Some of my favourite headlines end up being ones that disproportionately amuse myself”

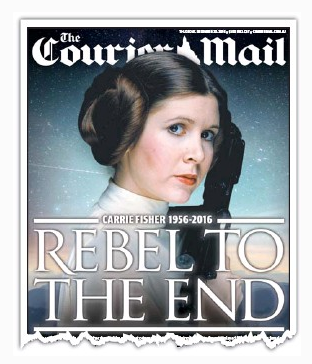

However, there are serious moments too, ones that hit you hard. It’s not a pun, nor even particularly clever, but maybe my proudest moment as a headline writer came just after Christmas in 2016, when the actor Carrie Fisher died. As a lifelong fan of Princess Leia, I was devastated. I was on holiday in my native Northern Ireland, sitting in a pub, when I heard the news.

Not long afterwards, Chris Jones – then deputy editor of The Courier-Mail, now editor – messaged me. The paper was splashing with the news of her death, needed an appropriate headline, and – despite my being on the other side of the planet – wanted me to supply it. I sipped my stout and ruminated as I looked out across the dark harbour, then beamed in a few suggestions. Soon afterwards, my phone pinged: there was a mock-up of the front page with my headline REBEL TO THE END. I’ve got a copy of that front page framed in my study at home.

What made you want to be a journalist in the first place?

I’m tempted to say the hours, the money and the fame, but no. It’s the chance to tell true stories. Thinking way back, the eminent BBC news presenter Martyn Lewis was a former pupil of my secondary school in Northern Ireland. I remember as a child watching him on television, thinking that if someone from the same school as me could ascend to the mystical realm inside the box in the corner of the room and make a living as a storyteller, maybe I could too.

But that notion waned and it took some time to rekindle itself: I became a journalist in my early 30s, and in those first days of my career, I was an arts and entertainment reporter. I couldn’t believe I suddenly had access to the storytellers I admired – artists, writers, comedians and performers – and could winkle information out of them about their craft, and help tell the story of their lives. I always had a curious mind, and I always wanted to know the behind-the-scenes version – and I’m the same now, with news stories. Give me all the details.

What are you most proud of about the stories you’ve told?

What are you most proud of about the stories you’ve told?

I’m proud of having given people a laugh or a smile with a clever headline. I’ll even take a groan. I’m proud of having helped people in some small way navigate through grief, or feel empathy, or come together to back a campaign. I’m proud of any time one of my headlines has elicited any kind of emotional reaction in a reader. With a good headline, you can give someone a cue about where this journey will take them, or signal to them how they’ll likely feel by the end, just with a few carefully-chosen words.

Also, I’m proud of being the ‘guy in the chair’, back at base – every good action hero has one. The reporters are those heroes – out on the road, often witnessing upsetting things, asking the tough questions, putting themselves in difficult and often dangerous situations. I’m there to support them and make them look good from my comfy chair in a temperature-controlled office, five metres from a kitchen stocked with industrial-size tins of coffee. It’s not such a bad deal.

What’s your message to Australians about why quality journalism needs their support?

Now, perhaps more than at any other time in human history, the truth matters, and people need to be educated and informed about what’s happening in the world. Without supporting quality journalism, you’re not getting information you can trust.

We’re being conditioned to expect to get our news free of charge on the internet, and people are wont to complain about paywalls and advertising and such, but many people don’t realise what a gargantuan effort and cost it takes to keep a quality newsroom running. Without support from the audience, that operation is eroded until it grinds to a halt. I always think of this reframing of the famous “First they came for the socialists” quote by Martin Niemöller – “First they came for the journalists … we don’t know what happened after that.”

“Now, perhaps more than at any other time in human history, the truth matters, and people need to be educated and informed about what’s happening in the world”

What’s the best thing about receiving this award?

It’s a privilege and honour to be chosen by the judges – some of the most esteemed people in the industry – as the recipient of a Walkley Award. Especially when it’s in recognition of my ability to write a pun that hopefully raised a chuckle in the judging chambers. Having been a finalist before, it was a thrill when my name was called, and I’m proud to be able to add “Walkley-winning” to my humble bio. I hot-desk at work, so I don’t have a permanent nook there, and thus the award sits in my study at home. Which brings me to the other great thing about it: it’s both heavy and pointy, making it excellent for home defence.

Read the award announcement here.

See all the 2019 Walkley winners here.

Baz McAlister is a writer and editor originally from Northern Ireland. He has worked in various roles at News Corp Australia over the past decade, including as deputy night editor on The Courier-Mail and The Sunday Mail, and editor of Qweekend.

He is a four-time winner, eight-time finalist and frequent MC of Queensland’s Clarion Awards. He won the 2019 Walkley Award for best Headline, Caption or Hook and was a finalist for the award in 2018.