Winner of the 2020 Pascall Prize for Arts Criticism, managed by The Walkley Foundation

Mireille Juchau, newyorker.com and The Monthly, “How Dreams Change Under Authoritarianism,” “Twilight Knowing: Jenny Offill’s Weather” and “Missing Witnesses: Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children’s Archive”

Novelist, essayist and critic Mireille Juchau won the 2020 Pascall Prize for Arts Criticism for a trio of essays published in The New Yorker and The Monthly.

“In a strong and diverse field of entries,” the judges said, “Juchau stood out for her insightful contextualisation of the work, elegant storytelling and depth of research. The Sydney-based novelist and critic’s standout review [“How Dreams Change Under Authoritarianism”] revisited a 1966 book about dreaming in Nazi Germany and considered the ways authoritarian regimes — past and present — can impact the collective unconscious.”

We spoke with Juchau after the Mid-Year Celebration of Journalism about the struggle to keep arts and literary criticism alive as government support and newspaper pages are slashed, the importance of having diverse places to publish, and the unsettling, prophetic tones of dreams under totalitarianism and in a global pandemic.

Congratulations on winning the Pascall Prize and joining some esteemed company. How does it feel to have that recognition for this body of work?

I’m actually delighted to be recognised by the Pascall Prize, especially because it’s valuing a specialist field that’s really under threat at the moment. And I’d love to thank the judges, the Walkley Foundation, and the Copyright Agency for supporting this vital work of arts criticism.

I’m really honoured to join an amazing list of my fellow writers who’ve received this award. People like Delia Falconer, David Malouf, Alison Croggon, and Andrew Ford to name just a few; it’s really wonderful to be joining them.

I work as a freelancer. I’m working in a precarious and a fast disappearing field, in arts criticism. The outlets are shrinking. It’s particularly bad at the moment because of COVID, and a lot of journals and publications have lost their advertising. Everything I’ve learned about critical writing has come from a lifetime of reading and seven years of university study, which I’m still paying off, so my work as a freelancer is a labour of love. It’s not an income. So I’m really thrilled that this award recognises that kind of deep specialist knowledge and distinctive voices and attention to language.

“We’ve just heard that the government has increased fees for the humanities in education by 113%… In my mind, it’s an ideological attack on critical thinking, creativity, and independent thought”

Arts journalism is often one of the first things to suffer when times get tough. What would you like to see as a potential positive future for arts journalism in Australia and its role in the media?

It’s really hard to be optimistic at the moment, especially on this really dark, dark day when we’ve just heard that the government has increased fees for the humanities in education by 113%. That’s where I got my education. That was my training to be a critic, an arts critic, and to see this happen is extremely disturbing.

In my mind, it’s an ideological attack on critical thinking, creativity, and independent thought at a time when we most need desperately need diverse, courageous, and distinctive voices. This is a government who prefers quiet Australians to people who have critical thinking and imaginative independence. So it’s very hard to be optimistic, but I guess my optimism comes from seeing the really hard work of writers around me, of the literary outlets that I publish in and that my fellow writers publish in, and how hard they’re working to maintain the space for this kind of work.

So places like the Sydney Review of Books that mentor new critical writers; and literary journals like Meanjin, The Lifted Brow, Island Magazine, who are really struggling to maintain their funding, to maintain their space for these kinds of writing. That’s where I get my hope, seeing the work that’s being done in those areas.

Also I get a feeling of optimism when I read the work of my fellow writers. Shortlisted with me was Melinda Harvey and Jack Callil, and I had read Melinda’s piece before, but my attention was drawn to Jack’s piece of critical writing, which I hadn’t come across, and reading their work was a [cause for] optimism. They’re both very fine writers. One is at the beginning of his career and the other is much more experienced. So that’s where I get my sense of optimism and a feeling of solidarity. There are people around me working extremely hard to keep this sector alive.

“The most important thing that good arts journalism and literary criticism gives us is a really acute attention to language and how language works in the culture. How it works to shape the culture, how it works to silence certain voices”

What is the importance of good arts and literary criticism, for you? What role does that play in a functioning society and a strong media?

I think the most important thing that good arts journalism and literary criticism gives us is a really acute attention to language and how language works in the culture. How it works to shape the culture, how it works to silence certain voices, restrict certain points of view, or open them up. All my university training has been about thinking about the way language works and having a critical eye on language, not just taking it for granted.

So, for example, recently seeing the Black Lives Matter movement has been really interesting. That has been a groundswell of protest that’s drawn our attention to what kinds of voices we’re hearing and what kinds of voices we’re not hearing; what types of language are acceptable in our media and other types of language that are deemed not part of that sphere.

This movement, I think it’s brought our attention to the way that certain voices are heard and some do not get heard. I hope that there’s more initiatives to let a more diverse range of voices into the media and give us a greater sense of that whole spectrum of experience here.

Looking back at the suite of three stories that were submitted for this award, are there any particularly juicy anecdotes behind the stories: how you stumbled upon the books or the works in the first place and how it panned out?

Definitely. I submitted three pieces, but perhaps I’ll focus on one in particular because it just seems such a perfect example of the need for a free press and also of the value of a literary education.

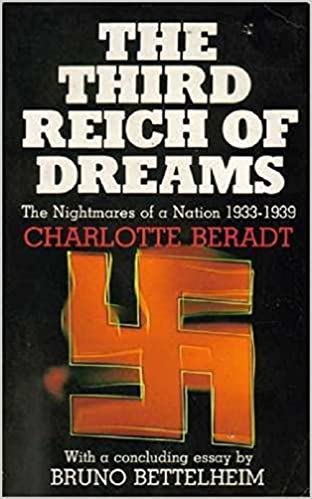

The piece I published in The New Yorker was about a book, which was published in 1968 but actually assembled during the Nazi regime in Germany, by a Jewish journalist called Charlotte Beradt. I just completely stumbled by chance on this book in my university library. Hadn’t heard anything about it, pulled it off the shelf, and was absolutely captivated by it. I had never read anything that combined social dreaming, the idea of social dreaming, with history as a form of testimony. But, also, throughout this book is this incredible critical mind that draws on works of literature to amplify the voices of the Germans that she interviews.

So Beradt interviewed 300 of her fellow Germans, and this was at great risk to her own personal safety. She was Jewish. She was a communist. She’d already been arrested by the regime. The Gestapo were doing house searches, so she had to keep her transcripts hidden in the spines of her own book collection and filed them in her shelves at home. And then when that became too risky, both to herself and the people she’d interviewed, she posted these transcripts to friends overseas, and it wasn’t until she fled Germany in 1939, reached New York that she retrieved all this material and set about writing this astonishing book, which is utterly unique, that combines dreams with political and social commentary and works of literature.

She draws on Brecht. She draws on Hannah Arendt, who was one of her circle in New York. And I guess in writing this piece, it reminded me of the importance of independent voices, distinctive voices, critical perspectives. That’s all brought to bear on her work. Also, she could only publish this work outside of Germany because as she was writing, as she was collecting the dreams, the Nazis cracked down on the free press. They shut all the Jewish press. They took over independent outlets and made them a kind mouthpiece for the regime.

“[Beradt’s book] is a really extraordinary account of the way totalitarianism actually impacts the life of its citizens”

So much of the book is a reminder of the importance of having diverse places to publish. And what she found through interviewing Germans about their dreams was that in the very earliest days of the regime, when people generally thought that there wasn’t an awareness of what the Nazi’s plan was for the Jewish people, through the dreams that she recorded, you could already see that neighbours were turning on each other, that Jewish people were being persecuted, that ordinary German citizens were starting to struggle with their conscience about things that they were required to do in daily life.

So it’s a really extraordinary account of the way totalitarianism actually impacts the life of its citizens. And that’s why I was really drawn to write about it. And also no one I knew had heard of the book, so it just became a passion project. I wanted people to read it. I wanted people to know about it. I guess my first hurdle was getting a copy, because the old copy I found in the library, when I read it, I was like, “I have to own this book. I’m going to cover it in post it notes and take notes on it.” I found a rare copy online, and then it was six months more researching Beradt’s life before I could start to assemble the piece itself. So the hurdles to me were time and money really, trying to put this together without any funding — eventually I got a little bit of funding to travel overseas and talk about it in Germany.

I’m still working on it, because I’d love to see this book republished in English, but the heir — the rights — cannot be found. There’s still a search on to find the person who owns the rights to the book so it can be reprinted in English. I was contacted after the piece was published in The New Yorker by a publisher in the UK who was really excited about this book.

Unfortunately, I had to bring him down by telling him that someone had already tried to find the rights holder, and the German publisher has been on the hunt for this rights holder for a long time because they owe them lots of royalties. And they haven’t been able to locate this person. They think he’s possibly deceased, but the book is still in copyright, so it can’t be reprinted.

This publisher in the UK, if he succeeds in finding the rights holder and he can go ahead with publication then he’d like to use my piece as an introduction, and I’d probably work on it a little more for that purpose. So my fingers are crossed that this mysterious figure will show up at some point and the book can be reprinted, or there may be some sort of legal clause that can be used to allow it to happen in the meantime.

So there were hurdles [to publication], but my hurdles were comparatively tiny compared to the immense courage and personal risk that Beradt went through to put together her work.

Mireille Juchau interviewed over Zoom

So this is a story that you think will continue on for you and you’ll continue working on?

Yeah, it’s an ongoing project, and there’s a personal connection for me because my great-grandfather worked for the Jewish press in Germany. And my great grandparents actually lived in the same suburb as Charlotte Beradt and went through a very similar experience — leaving, trying to leave — but they weren’t able to leave Germany. So there’s a lot of personal connections to the Jewish press and to this part of Germany and that experience of persecution and thinking about what totalitarianism does to the private self.

Your piece in The New Yorker drew subtle but effective comparisons between that book and its subject matter and the current reality in America, in particular.

Yes. And since I published the piece, I’ve had a lot of people contact me, letting me know about their projects collecting dreams under Trump. There’s quite a few different groups and individuals who’ve gathered dreams of American citizens, and undocumented migrants as well, and what they’re dreaming of under Trump.

Some of those are really quite eerie and fascinating and hilarious and disturbing. And so I imagine there’ll be some sort of, I mean, some people have kind of already put them together on websites, but I imagine that at some point we’ll see a future book about that particular phenomenon.

I know pandemic dreams have been a big thing lately as well, so people are becoming interested in them. And I think what struck me about Beradt’s book was she was really ahead of her time, and I suspect that’s why she didn’t get a lot of notice when the book came out. She was writing history with material that couldn’t be considered completely factual.

She was using dreams, and not just dreams but the recounting of dreams. At the time when she was writing, in the ’40s and ’50s, there was still a need for purely factual material about the Holocaust in order to indict people, in order to seek justice and reparation. And so anything that wasn’t completely provable or verifiable was probably given less attention, and I suspect her work fell through the cracks because she was doing something very different.

When I read her book, I thought immediately of Svetlana Alexievich, who won the Nobel Prize for her distinctive work on Russia and Chernobyl. I think they were working in similar terrain — that Alexievich was interested in the history of feelings, which is not something you can verify or prove. It’s an experience, but it’s just as legitimate as other forms of history. And also, Beradt was a woman, so I suspect her work wasn’t seen as being as serious or impactful as maybe some of the other works coming out in the early days after the Second World War. But yeah, I think it’s utterly compelling and fascinating and I’d love to see it reach more readers.

For you personally, what significance does receiving the Pascall Prize have in light of the body of work that it was awarded to?

It gives me a feeling that my work is valued by esteemed writers that I work alongside. It gives me a feeling of hope for the future work that I can do, that it will be recognised, read, received. It gives me a feeling that I’m part of a community of writers, and that’s really important because writers work on their own. They labour over works for months without necessarily speaking to people about them.

We’re often working in solitude just by the nature of our work, and also these days there’s so little permanent, full-time work on publications. There barely are any for arts critics, so we’re often working in solitude, and the feeling that there is a community around me of writers who value the work that I do is really absolutely inspiring and comforting. It gives me a great sense of hope.

I’m still gobsmacked by the announcement this morning about the education sector, because I’m keenly aware that I wouldn’t be where I am now without the education that I received. I did a communications degree, a year at Sydney University, and I did three years of a PhD, and the teachers that I had gave me everything that I use today when I’m working.

They taught me critical skills. They taught me to read between the lines. They taught me to think about language in a particular way. They taught me to value imaginative independence. And so to see the fees for that sector be increased, it makes me wonder whether I would have been able to afford to do the study that I did.

Since I’m still paying off my study now at the age of 50, it also makes me realise that it’s just going to create more barriers to education for people who would benefit from it. So I celebrate these awards for reminding us that this is a really important field of practice, and it deserves to be funded in as many ways as possible. Education is number one. The number one route to becoming an art critic is education.

Mireille Juchau is a novelist, essayist and critic. Her third novel, The World Without Us, was published internationally and won the 2016 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award. Her essays are widely published, most recently in newyorker.com, LA Review of Books, LitHub, The Monthly, Tablet and Best Australian Essays. She has a PhD in literature and has taught at universities and in the community. In 2018 Mireille was writer in residence at the Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, researching her next novel on epigenetics and historical memory.

Watch interviews with the winners of the 2020 Mid-Year Celebration of Journalism

Read all the winners of the Mid-Year Celebration of Journalism Awards here.